I have a few larger things underway for next week, but in the interim a few notes on systemic risk things I've been thinking about.

01. Nuclear AI and the Collapse of NFTs

In a two-part series here we recently wrote about Stanley Jevons (Part 1/Part 2), and the idea of Jevons' paradox, how gains in efficiency are sometimes offset by increased usage. This is especially problematic in energy, where gains can be counterbalanced, sometimes completely, by increased usage.

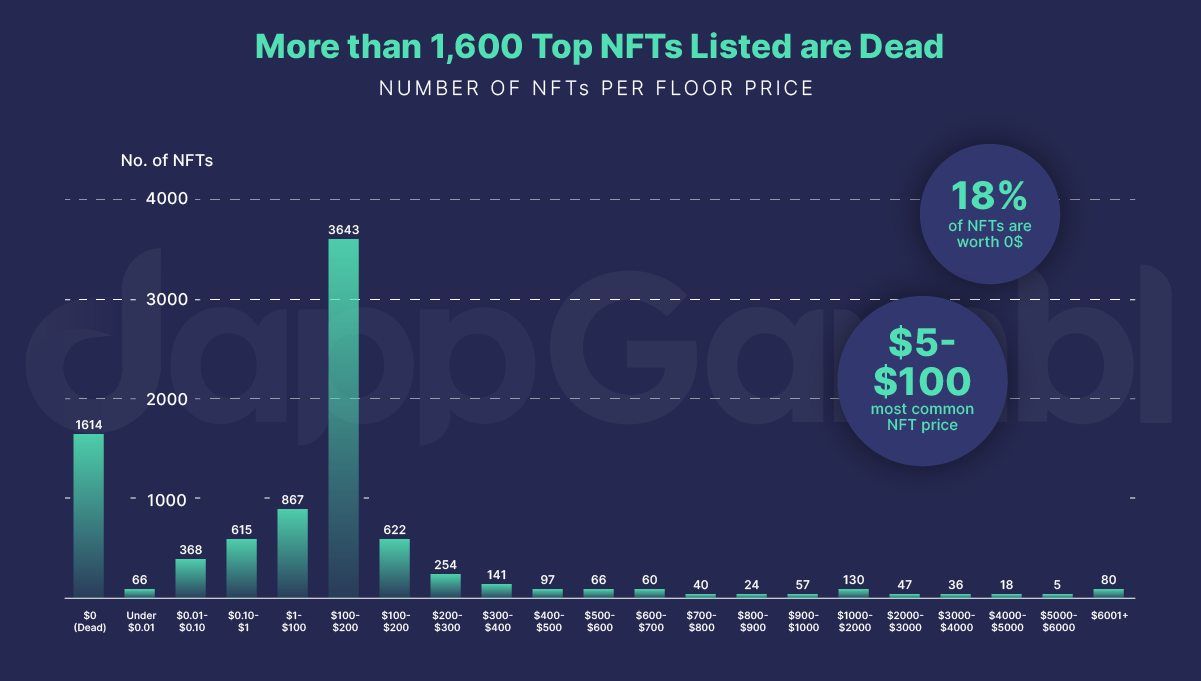

Two recent examples came to mind, both of which very problematic. First was some work arguing that NFTs (those highly-promoted electronic tokens built around crypto) have largely collapsed, with thousands having no value, and many illiquid with no owners.

The piece goes on to argue, somewhat speculatively but likely directionally correct, that the energy required to create these NFTs is the C02 equivalent of 16,243,017kg of CO2 which is roughly the yearly emissions of 2048 homes. This energy wastage is massive, and a byproduct of what briefly seemed to be high returns to this malign use of energy.

Something similar is happening in AI, where training models and then responding to queries and prompts, are both highly energy intensive. Academics have been wrestling with energy costs of large language models for some time, and there is a large and growing literature on the topic, but we won't get into that here.

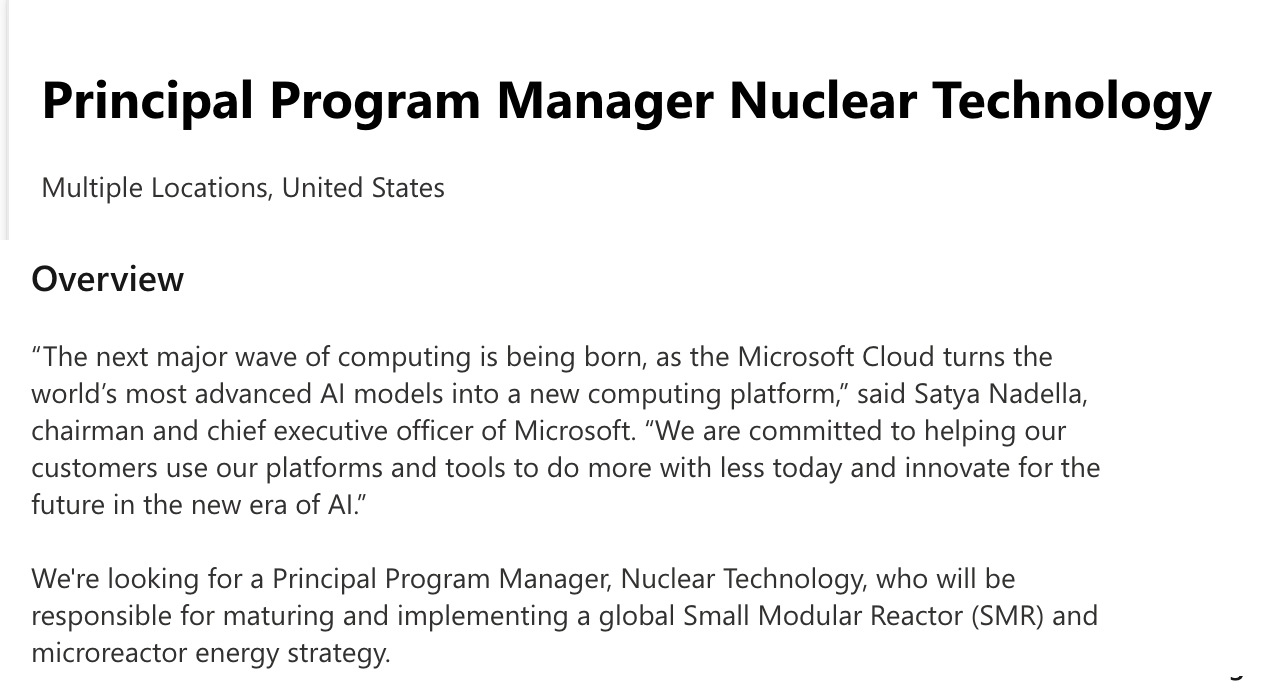

Instead, let's look at the problem from the other end of the telescope, at how companies whose businesses are predicated on these models are behaving, and what that implies for any rebound in energy use. And we have a terrific example this week, with a Bloomberg piece reporting on how Microsoft and others are shifting to think more seriously about nuclear power, to the point that the company put up a job posting for someone to run its nuclear power efforts.

As the Bloomberg piece says, Microsoft is hardly alone in realizing its ramping energy needs, but given its relationship with the wildly popular energy sink also known as OpenAI, its soaring energy needs has it casting about everywhere for new and stable sources.

This is, of course, very much in the Jevons frame: Higher returns to power usage in an increasingly renewables-driven energy system are driving new uses, which in turn creates a new and higher power baseload, which in turn means that the production must be stable and continuous, making technologies like nuclear more desirable. A more efficient energy system is driving new uses, creating a higher load, offsetting gains elsewhere, with systemic consequences.

As I said to a colleague recently, we aren't even running to stand still properly.

02. Florida Home Ownership

Any time there is a natural disaster—whether fires in California, tornadoes in the Midwest, or hurricanes in Florida—there are predictable calls for hardening infrastructure. Understandably, people think there must be ways to make homes, roads, industry, etc. more resilient to these shocks.

This is makes sense given billions of dollars (and growing) in annual damages, and it is not a new realization, so it is well understood by regulators and insurers. It is worth considering how the interplay between these various risk factors has played out. In short, how is hardening going?

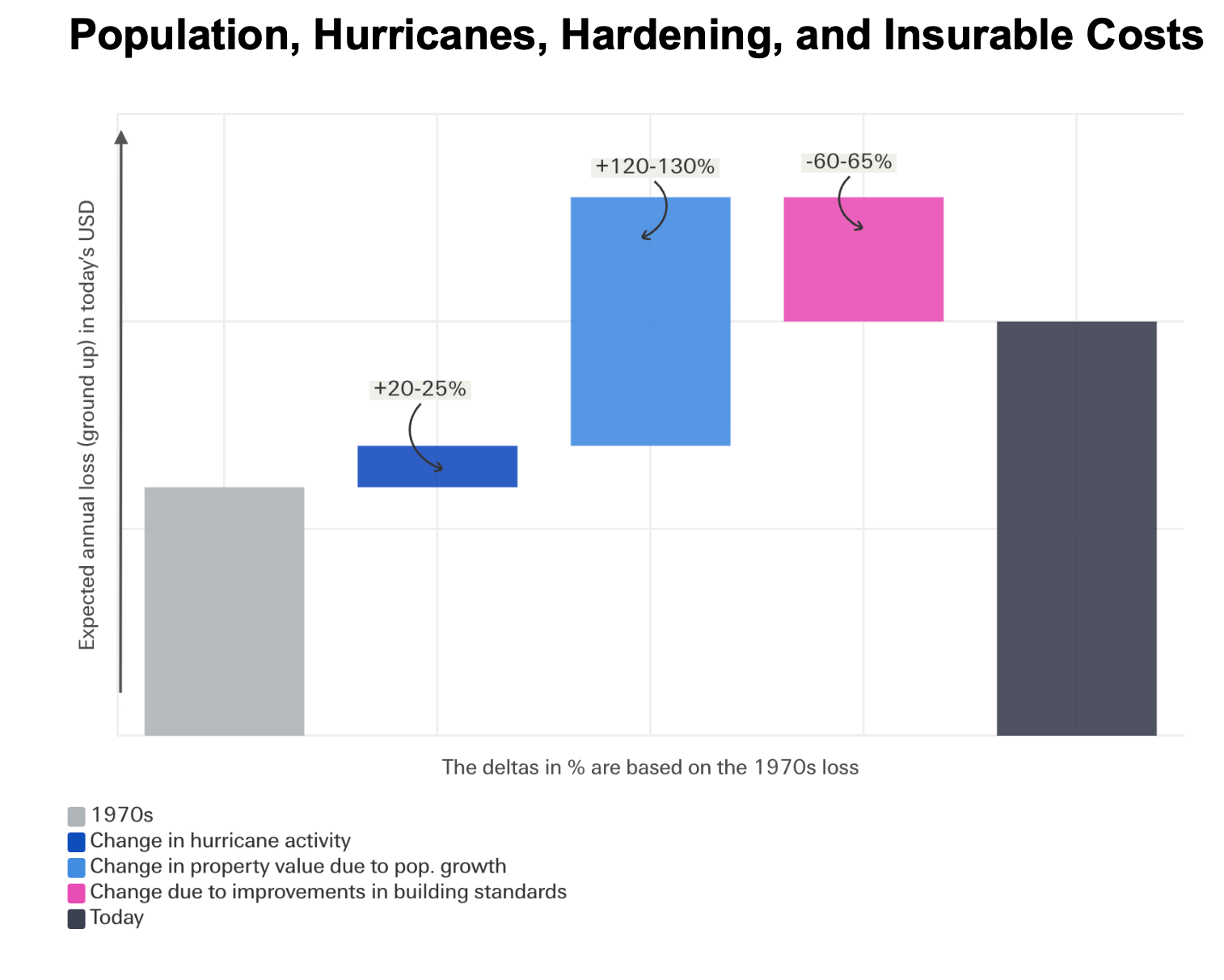

In a recent report on the fallout from Hurricane Ian, reinsurer Swiss Re considered what the damages would have been if the hurricane had struck 50 years ago. Its answer: "Insured losses from a storm like Hurricane Ian, had it struck Florida a half-century ago, would have been far lower than they were in the current environment". In other words, despite hardening infrastructure immensely since then, and despite better forecasting, models, and building regulation, the inflation-adjusted costs are higher now than then.

Why? The central factor is obvious: Population growth. More people means more infrastructure, which means more insured things that can be damaged and must be repaired. While storms have increased in frequency and severity over the period, Florida's population has soared. There are currently around 22.24 million people living in Florida, up from 4.95 million in 1960, a nearly five-fold increase.

In the following figure Swiss Re tried to untangle the relative effects of infrastructure hardening, population growth, and hurricane severity. What it shows is that all of the gains, and more, from improved building standards have been offset by a higher Florida population. In other words, buildings are better, but losses have soared because the population has soared.

While Swiss Re doesn't get into it in this report, it is an interesting example of the controversial topic of risk homeostasis. This is the idea that people adjust their behavior in the face of risk reduction technologies, such that their total risk exposure "feels" more or less the same. While controversial, there is likely an element of risk homeostasis in what has happened in Florida: If recent hurricanes struck a Florida with 1960s buildings codes the damage would have been extreme, perhaps discouraging people from moving there, or causing others to leave the state. Better building codes and less damage, crossed with insurance recoveries, allow people to feel as if they are managing their risk exposure in a way that permits some risk homeostasis.

This is speculative, obviously, but the broader point stands: It is very hard, if not impossible, to harden a system's way out of risk given how humans respond via higher population growth and relocation. We have seen this in California, where better building codes have caused people to move into wildfire-prone regions, causing insurers to exit the state, given that their insured risk exposure was going to climb, even if with the better fire standards given more people exposed to more risk.

Again, we are running to not even stand still.