Everyone loves a good arb. In finance, arbitrage opportunities—the same asset selling for different prices in different markets—are prized: risk-free profits await. Simply sell the expensive version, buy the cheap one, and wait for the money to roll in.

The reality of running an arb is more complex than casual language would suggest. In particular, in the real world there are limits to arbitrage, which help explain why apparent mispricings persist in markets, sometimes for a very long time.

To see why, it helps to understand the (many) limits to arbitrage.

The Limits to Arbitrage

Efficient markets theory tells us that prices should quickly adjust to reflect all available information, eliminating any arbitrage opportunities. But that doesn't always happen, even if it isn't a terrible first approximation, and that can lead to arbitrages.

Why don't prices always converge? Well, here are some of the main factors from the academic literature:

This isn't a finance paper, so I won't go into these factors in much detail. The upshot, however, is that all these factors introduce friction in the market, allowing apparent mispricings to persist. There is much academic research on this topic, much if building on a classic paper (from which I cribbed the title of this post). More recent work extends this, introducing, for example, "noise traders", people who kinda DGAF about fundamentals, but buy and sell based on whims, vibes, momentum, and the like, which can, at enough scale, cause prices to do weird things, thus limiting arbitrage.

Case Example: Arbitrage in Prediction Markets

Prediction markets have been having a moment recently, with them cited increasingly regularly about sports, economic indicators, and US election prospects.

Critics like to point to how prediction markets get things wrong all the time, like Brexit, or the election of Donald Trump in 2016. Or Josh Shapiro as Kamala Harris's pick for VP in the current cycle.

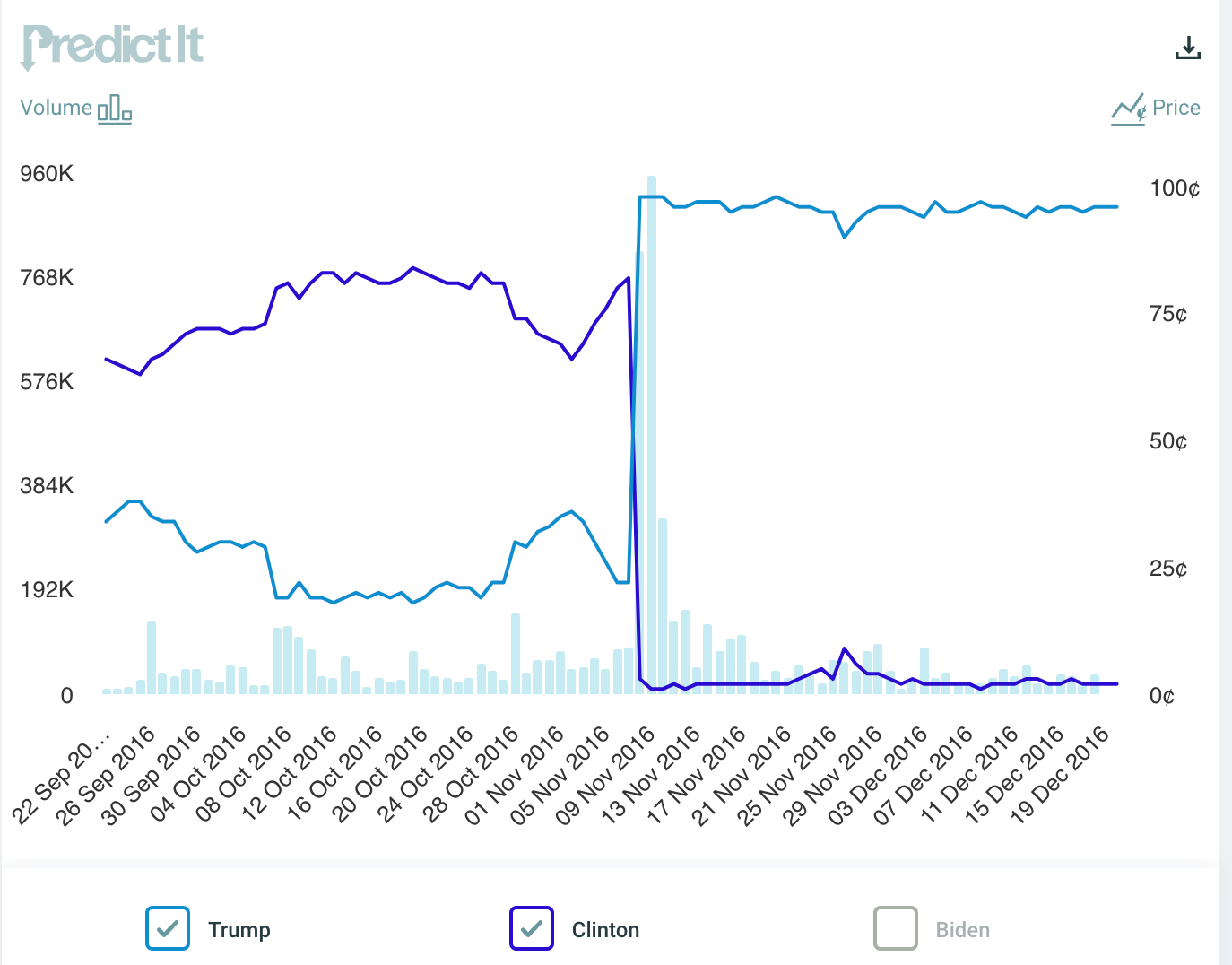

Here is the PredictIt graph from the days leading up to the 2016 US election. While perhaps not as wildly off as some pollsters were, prediction markets had Clinton as prohibitive favorite, which she was, based on polling data. But Trump's likelihood was nowhere near zero. Not even close.

Prediction markets are wrong all the time, as above, but they are, in a sense, wrong by design. Such markets are giving likelihoods for things, not guaranteeing outcomes. They might better be named likelihood markets, not prediction markets: they are attaching likelihoods to outcomes, not making predictions.

Let's now reconsider the above 2016 graph. Yes, Clinton's winning likelihood averaged around three times that of Trump's for most of the period prior to the election. And then he won, as you may recall.

But does that make PredictIt wrong? No, not in practical terms. First, a 34% pre-election chance of Trump winning is not only not zero, it is ... high: You wouldn't board a plane with a 34% chance of crashing, for example. Second, these are likelihood markets, not certainty markets. If something has a 34% chance of happening, you would expect it to happen roughly one out of every three times. Such "unlikely" events happen all the time, predictably so.

Arbs and Kamala Harris for President

Let's now turn to prediction markets in the current U.S. election. There are more prediction markets now than in 2016, and they are generally more liquid, even if not as liquid as orthodox financial markets. We should still expect them to come to similar conclusions on similar predictions.

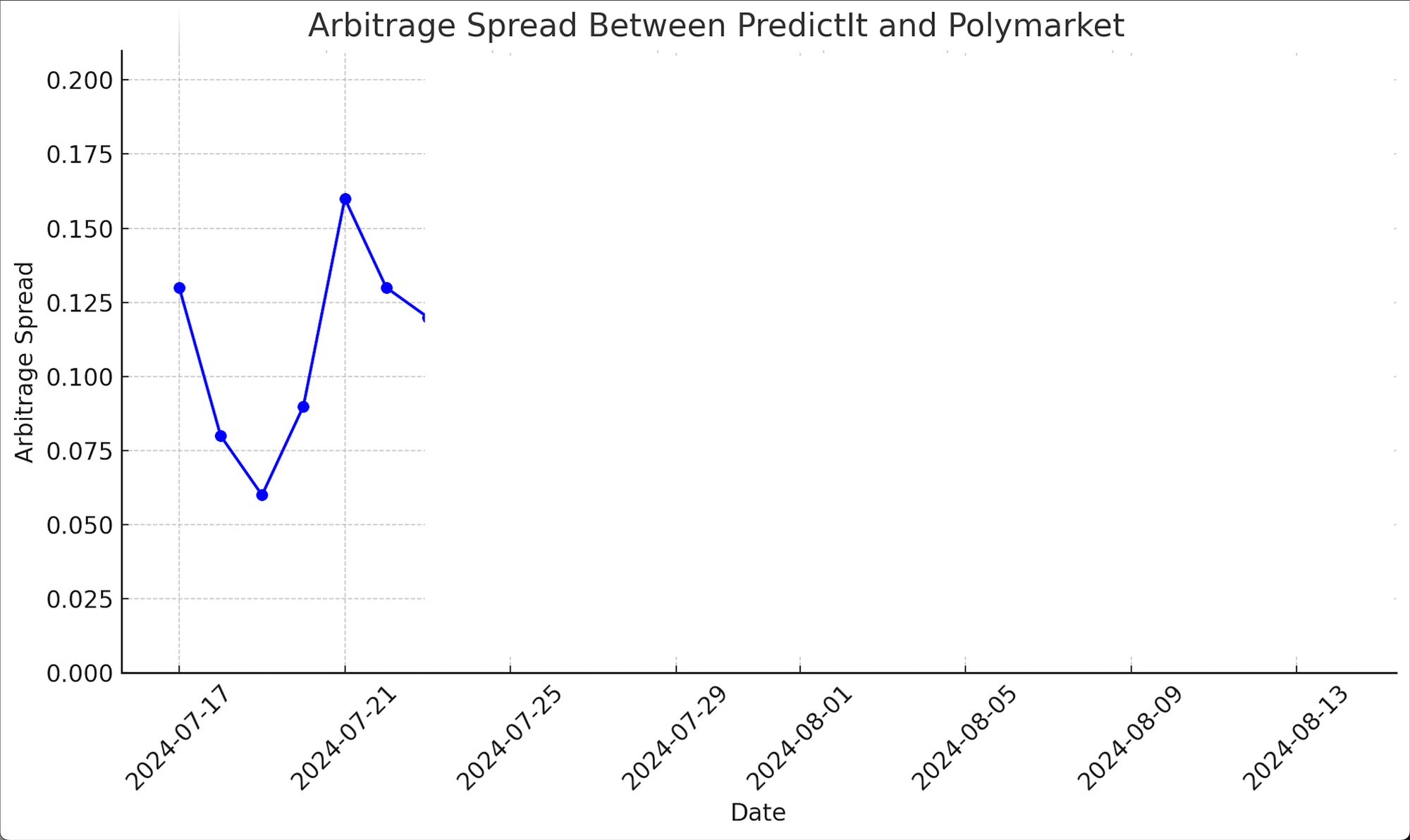

Do they? Not so much. A week or so ago I started looking at two of the most popular prediction markets—PredictIt and Polymarket—and their prices for Kamala Harris for president (KFP) 2024. At that time the markets looked like this:

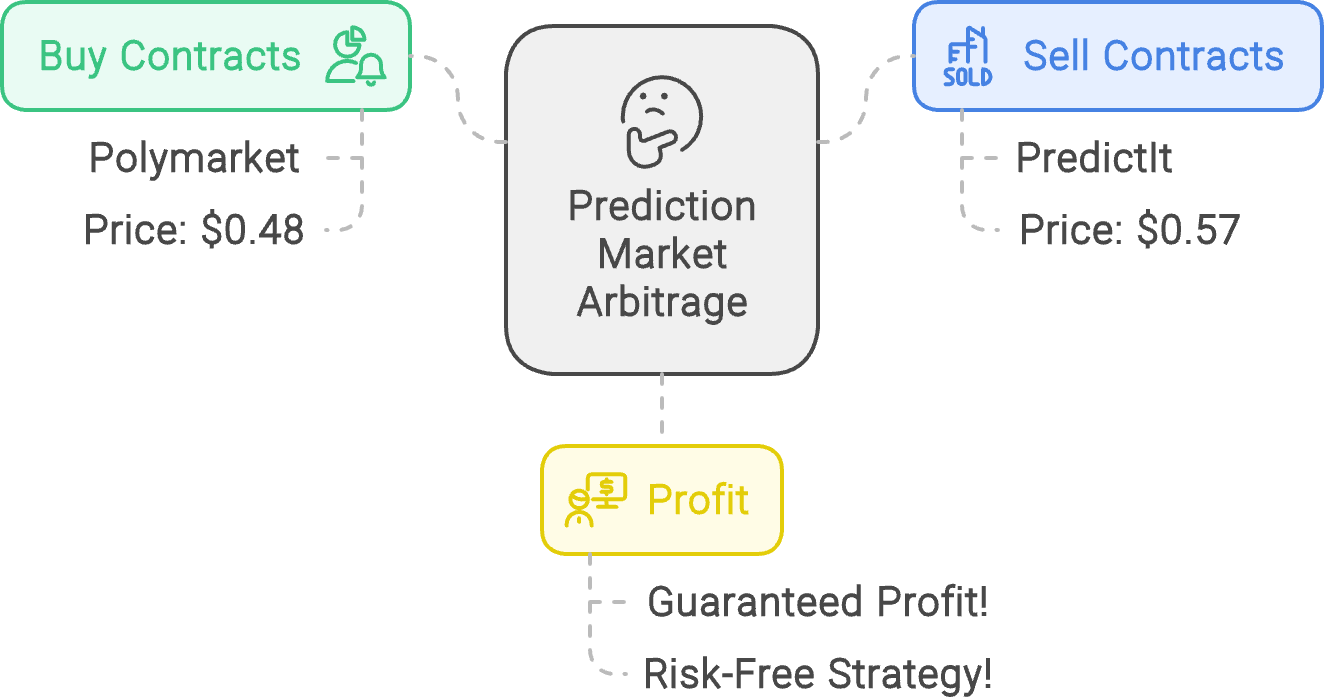

That 9% was large. If a stock was listed in two different markets and was trading at the kind of difference it would be free money. Because when we see the same asset trading for materially different prices in two different markets, we know what to do! We arb the shit out of it and make bank.

Intrigued, I checked how the spread between the two popular prediction markets' prices had trended up until that point. Later we will look at what has happened to prices since, and what that tells us about prediction markets.

So, clearly, an arbitrage-aware investor should have done some version of the following:

Weirdly, this didn't happen. I kept looking at the prices, seeing the persistent difference, and wondering what was going on.

The Limits to Prediction Market Arbitrage

So, why was the KFP arb seemingly not on, and what does it tell us about prediction markets? Before answering, it is worth pointing out that participants were baffled too. The comment section on the Polymarket site—please do not, for the sake of your sanity, go there—regularly featured anonymous participants pointing out that Polymarket's price seemed bafflingly low, given polling and PredictIt pricing. (Commentors also pointed out that whoever it was that had Michelle Obama for president trading above zero was handing money to strangers, but that is a different prediction market problem.)

In my brief and uncomfortable scanning of the comments, however, I discovered I was wrong. A large fraction of the comments, perhaps the majority, were from people unhappy at the prediction that the market had come to. These participants, generally speaking, had not bet, seemingly had no plans to bet, and were mostly just angry at the prices. They were regularly being told to either place a bet or leave.

Such behavior struck me as similar to standing outside the NYSE and shouting at the stock market, but having no money invested. Maybe consider taking up stamp collecting, if that still exists.