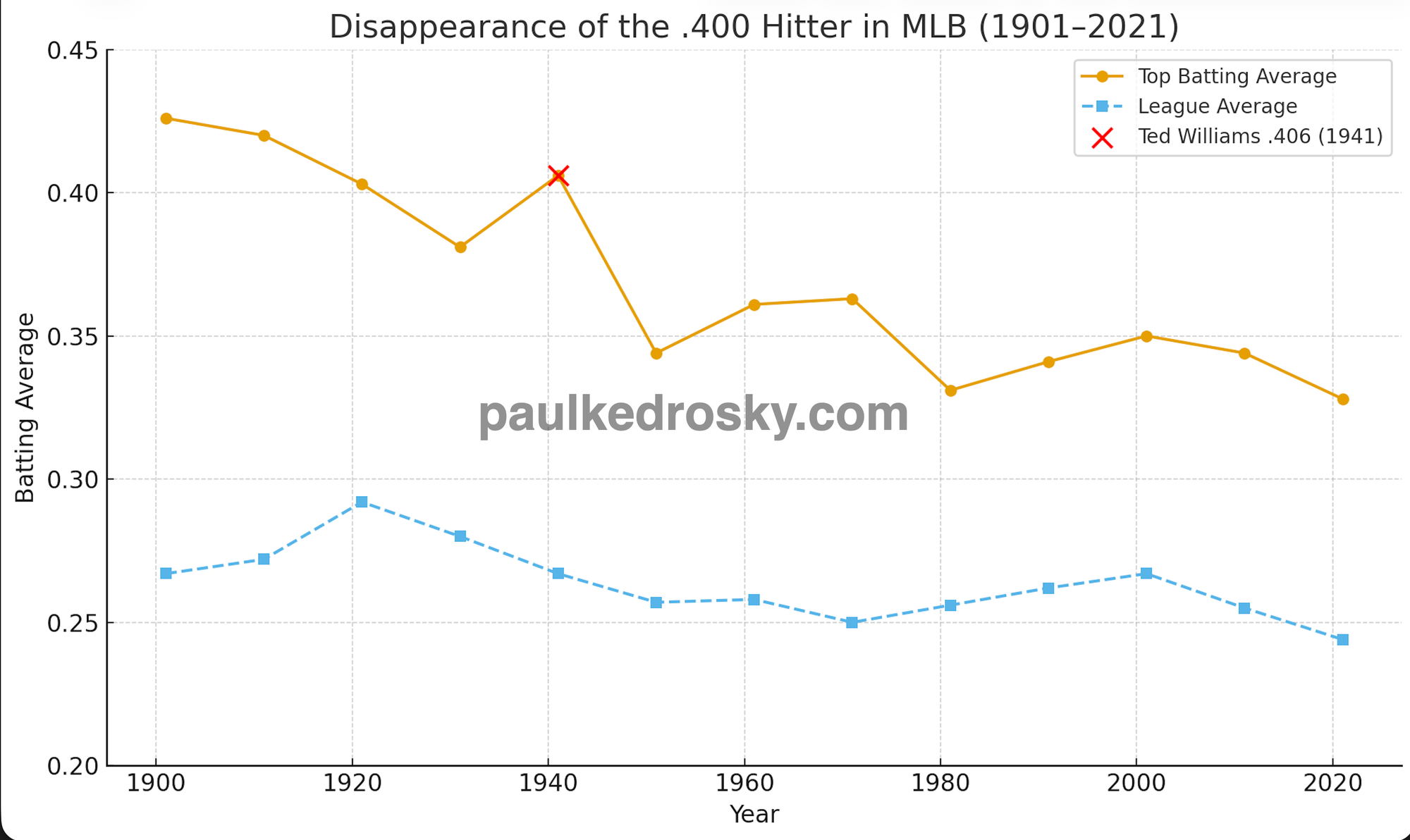

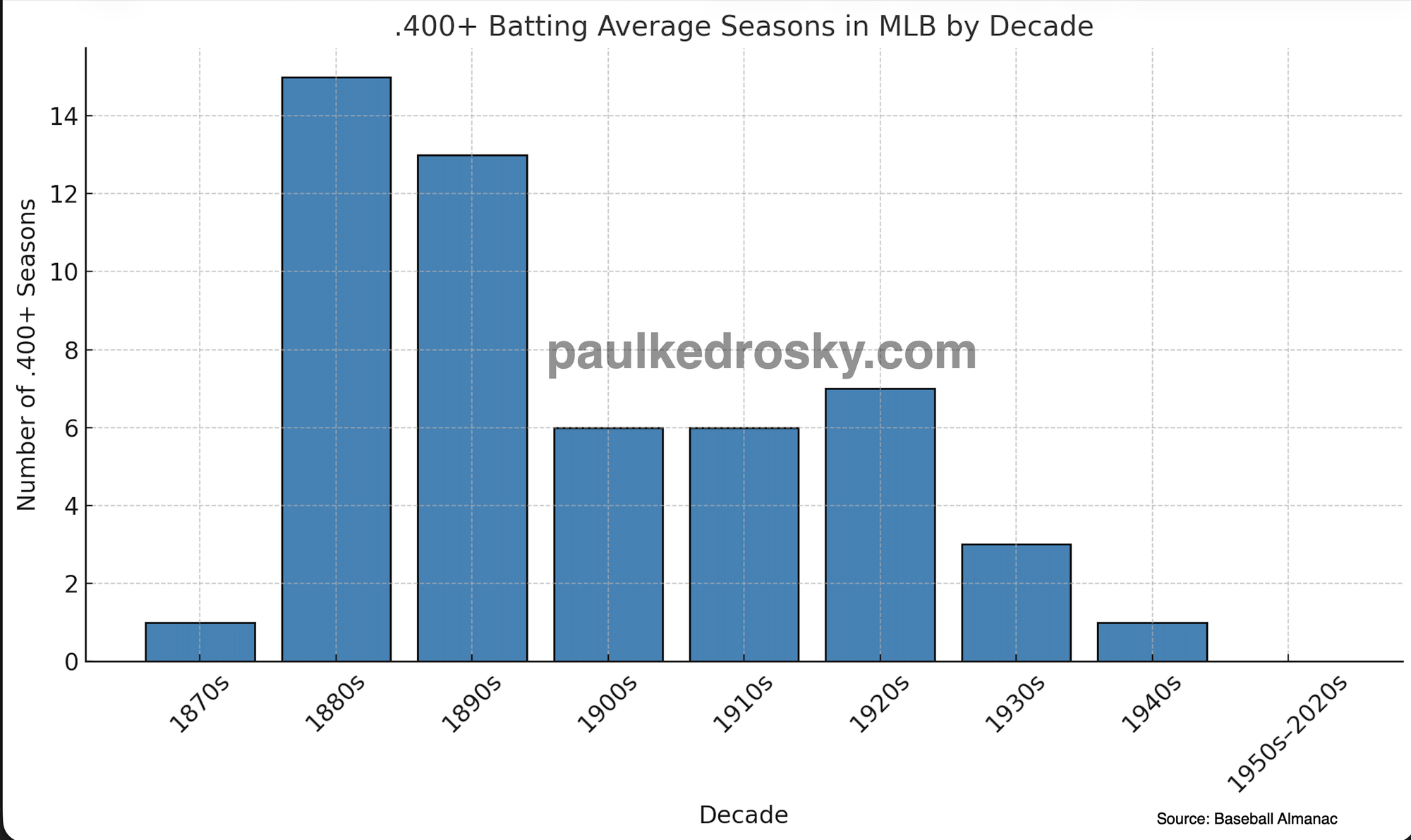

Giants once roamed the earth. There was a time when baseball produced .400 hitters—Ted Williams in 1941 being the best-known example, although others dotted the decades before. Since then? Nothing. No one has come very close. Batting averages hover, despite everyone training better, scouts scouting better, players being fitter and eating better. And yet, the .400 hitter is extinct.

Evolutionary biologist and baseball buff Stephen Jay Gould wrote about this in his book Full House. He argued that the disappearance of .400 hitters was not because players got worse but because they got better. The performance distribution had a higher mean, and the variance had shrunk. As median player skill rose, the right tail of performance became less populated. Baseball lost the illusion of extraordinary players because variance collapsed against a higher baseline. Outliers were no longer visible.

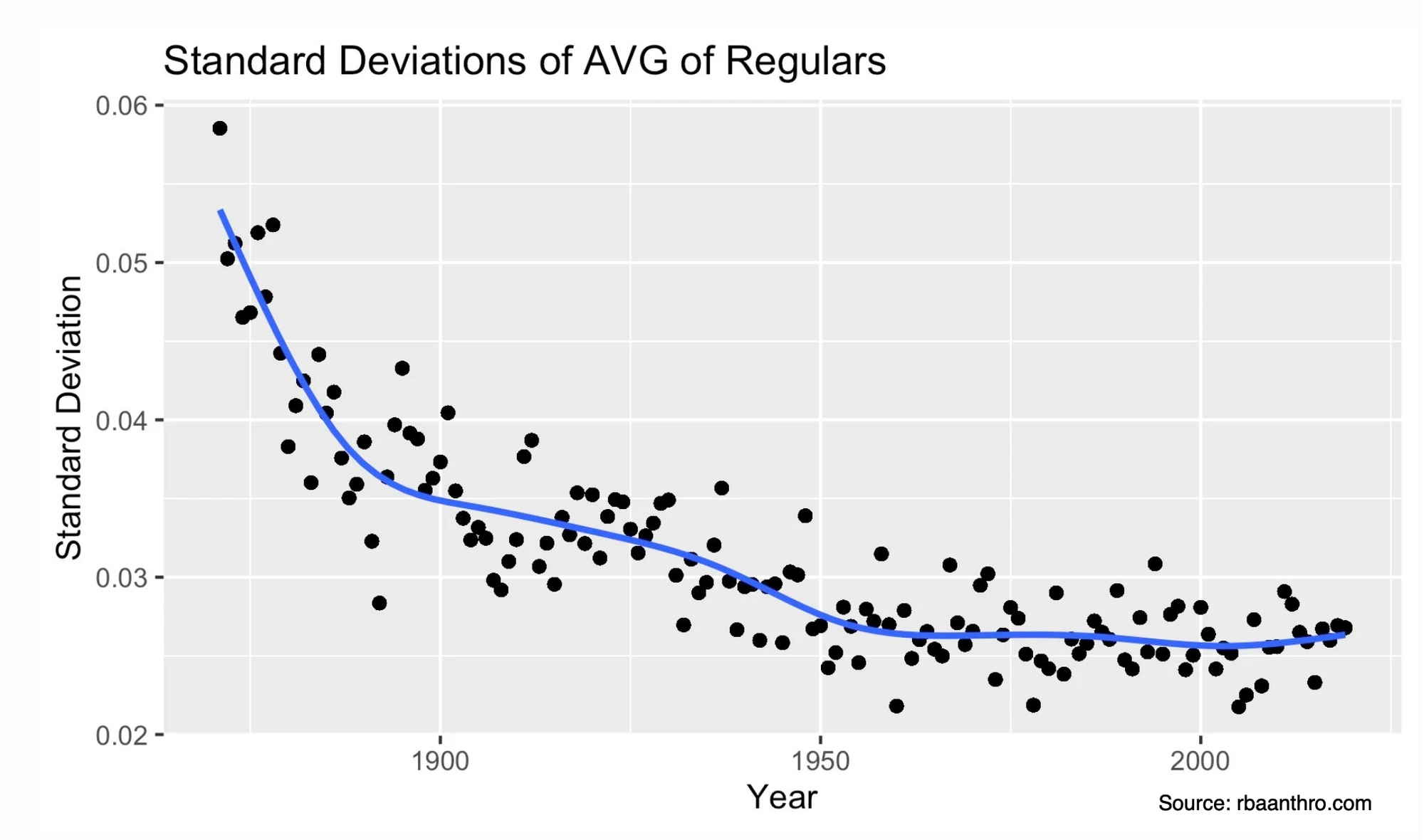

You can see the multi-decadal decline in batting variance in the following figure. Over the last hundred years, variance has collapsed.

Higher mean performance and collapsing variance isn’t just a baseball story, even if baseball is instructive. Whether we're talking about sports, evolution, or society itself, it is a model for how societies evolve under conditions of rapid baseline improvement. The arrival of large language models (LLMs) is just such a moment, transforming how we think about talent, creativity, and progress.

The Vanishing Outlier

Gould’s insight was deceptively simple: when overall competence rises, exceptional-looking performances can vanish. The ceiling does not go up as much as much as the floor does, so the distribution tightens.

In baseball:

- 1900s–1940s: Wide variance in player preparation, diet, and training meant outliers—people who hit far better than peers—were visible.

- Post-1960s: Weight rooms, analytics, nutrition, and scouting systems all converged and became best practices. Everyone became better trained, so batting averages compressed into a narrower band.

This is why Williams’s .406 season in 1941 looks unrepeatable: not because modern players are worse, but because they are better—collectively.

The moral: extraordinary outcomes can (seemingly) disappear when the baseline rises because everyone is better.

Tadej Pogačar and the Illusion of Dominance

But there are subtleties. Cycling provides an example of how compression reduces outliers, but they don't go away. A century ago, Tour de France stages routinely broke riders; “bonking” (running out of energy) was common. The winner was sometimes an hour ahead of everyone else. Nutrition was poor, recovery nonexistent, training haphazard. Variance was wide.

Now, enter multiple-time world champion and serial Tour de France winner Tadej Pogačar, the Slovenian superstar. He dominates pro cycling, despite a modern peloton baseline that is extraordinarily high, the product of science, training, altitude camps, nutrition, power meters, and so on. The entire field has compressed upward.

You can see that rising baseline in the following graph of average speed¹ over the last hundred years.