The U.S. Federal Reserve's Beige Book is, by design, boring. It generally contains a soporific mix of anecdotes, data points, and econo-flotsam from the twelve Federal Reserve districts ... and anyone who says they read it regularly is not to be trusted.

But the just-released August edition was ... almost readable! Why? Because data centers were the only non-tariff refrain in the Beige Book, and they were the main source of regional economic growth.

Here are some data center-related examples in the latest Beige Book, by district:

Philadelphia (Third District)

- Nonresidential construction is weak overall but data centers and related power generation projects are moving forward.

- Developers increasingly use escalator clauses and larger contingency funds to handle tariff-driven data center cost inflation.

Cleveland (Fourth District)

- Increased demand in nonresidential construction tied to data center projects and upgrades to existing facilities, despite otherwise flat demand.

- Expected continued demand growth in data centers.

Chicago (Seventh District)

- Nonresidential construction is supported by strong demand for data centers.

- Contractors are pre-ordering materials to lock in costs amid tariff volatility.

- Data centers stand out as one of the few consistently strong segments in construction.

Atlanta (Sixth District)

- Electricity demand growth caused by data center activity.

- Freight movements tied to data centers are helping offset weakness everywhere else.

Kansas City (Tenth District)

- Higher regional energy demand from data centers.

Nationally, the report noted a “surge of data center construction”, a rare bright spot in commercial real estate, in particular in the Philadelphia, Cleveland, and Chicago Districts. And, not surprisingly, it cited sharp related increases in energy demand, in particular in Atlanta and Kansas City, due to data centers significantly causing a step increase in regional electricity loads.

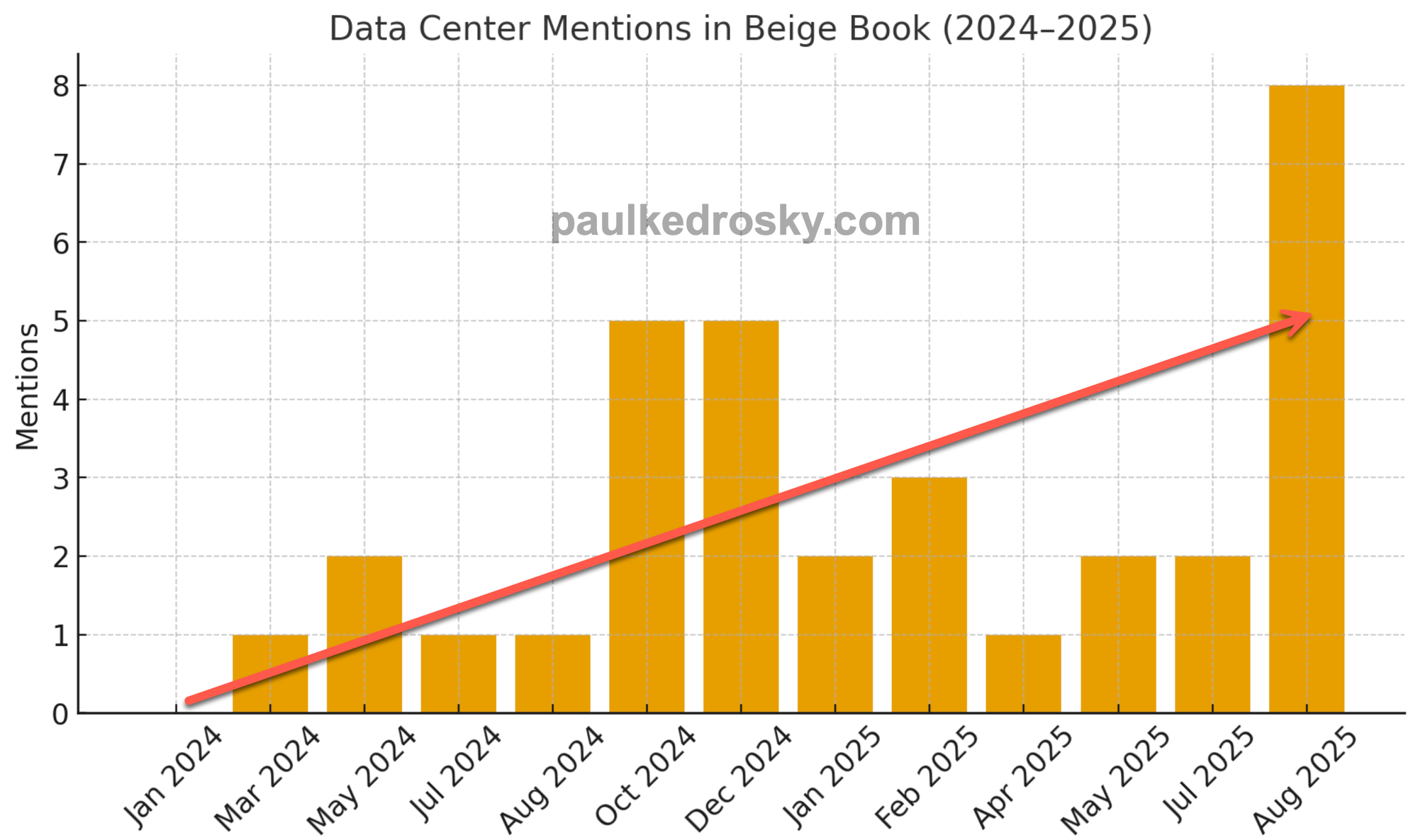

To put this in a kind of context, here is a graph of data center mentions by Beige Book edition over the last two years. I have added a helpful up-and-to-the-right arrow to the figure

While remarkable, this will come as no surprise to regular readers of my work here. See here, here, here, and here, for just some recent examples.

In those, I've argued four things:

- Data center spending is so large as to be altering quarterly GDP growth.

- Increasingly exotic debt structures underlie a growing share of the spending.

- The shift from training to inference is now past 50/50, and it will reduce the demand for the latest GPUs.

- Power is likely to be the most important gate to continue spending at this rate.

PJM and Powering Data Centers

Turning to power, we are already beginning to see the kinds of weirdness and general screwing about that you would expect in an energy grid at the edge and under immense stress. The tension is that data centers are profitable and predictable customers, but they also represent step function load increases in a system that can't smoothly add new sources of power.

Consider the case of regional interconnect provider PJM. This week its attempt to allow data center customers to join the grid cheaply blew up. It wanted to classify new data centers as “non-capacity-backed load” (NCBL), which would make it possible to the during load emergencies. In exchange for this, they would get lower connection prices.

Win-win, right? More paying customers connected to the grid, but no guarantees of supply, a big deal given the energy supply deficits ahead.

Not surprisingly, it didn't work. The proposal collapsed almost immediately under the weight of broad opposition during a comment period. For a region wrestling with tens of gigawatts of new digital load, the idea looked like a shortcut—speeding connections without adding supply—but it was largely viewed as both unworkable and unlawful.

Data center operators called it jurisdictional overreach, impossible to reconcile with 24/7 uptime guarantees. Market monitors warned it would wreck price signals and shift costs onto others. Utilities and independent producers labeled it a premature, out-of-market fix to a problem that PJM hasn’t clearly defined. Even state governors pushed back, arguing that it risked unintended consequences for reliability and planning. And ratepayers figured, rightly, it would turn into higher prices for them.

What this episode underscores is how bananas things have become in data center world. Providers want them as customers, but struggle to cope with their huge increases in load, given the decadal supply lags for any material power supply increases. This doomed proposal becomes, in this light, more like a cry for help: the region knows it faces 10–30 GW of new demand but lacks the capacity to absorb it. It was like a desert community, desperate for more property tax income, allowing a 10,000-home exurb to connect to the water supply—if it would agree to no water during droughts. Yeah, no.

Data centers have put the energy system under extreme stress, and it is showing up in unexpected places, from the Beige Book to doomed power curtailment proposals from interconnect providers. Speaking for myself, however, simply making the Beige Book worth a look is, for now, a small win.