What if he's right What . . .if. . .he . . .is . . . right W-h-a-t i-f h-e i-s r-i-g-h-t

—Tom Wolfe, The new life out there, New York Herald Tribune, 1965

There is a growing sense that chat—as in ChatGPT—was an error. For two recent examples, see here and here. Neither of these are from people from whom I would take advice on anything consequential, so I am, if anything, biased to think they're wrong. But, to quote writer Tom Wolfe on Marshall McLuhan, "What if he's right"?

Let's start with something that too often goes unsaid, but helped drive ChatGPT's unprecedented adoption (which came as a surprise to OpenAI as much as anyone). And it is this: Humans are hairless, gregarious apes. Humans, and their fascinations, cannot be understood without our tireless and sometimes lethal compulsion to talk.

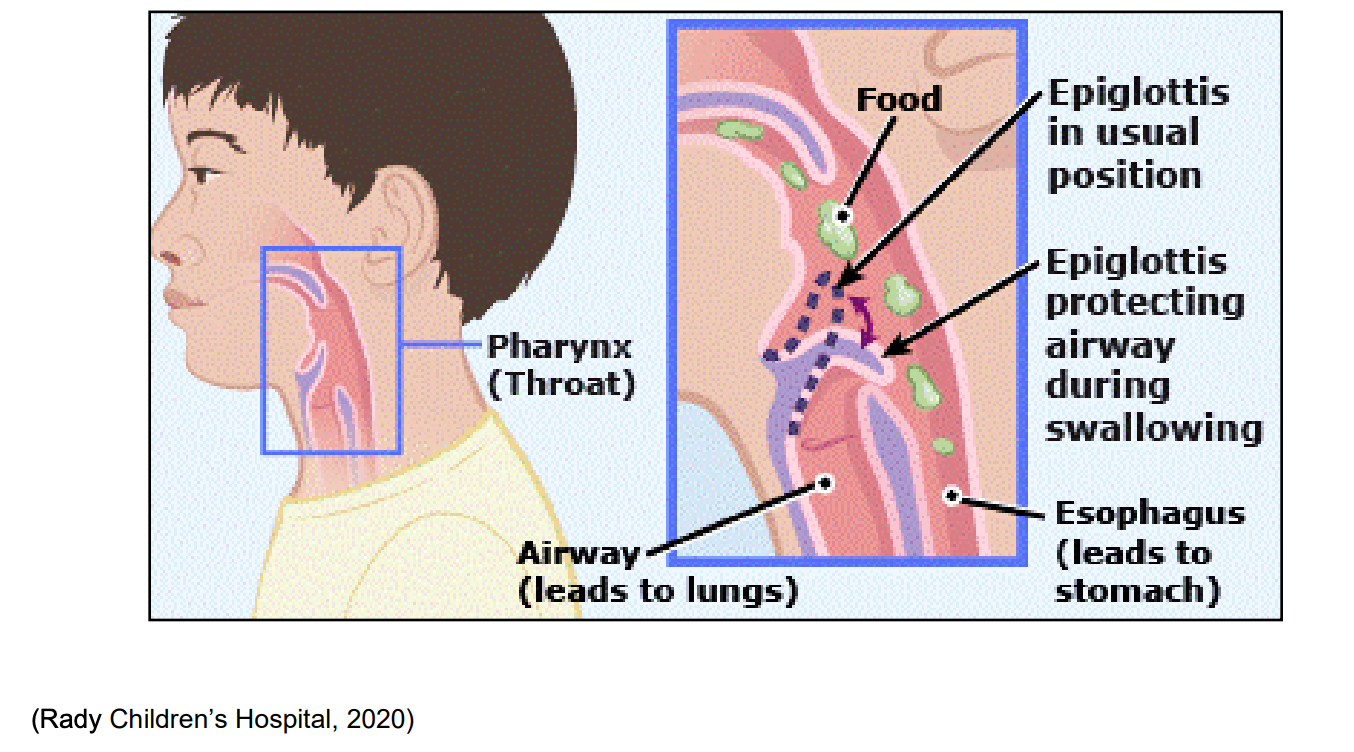

Why lethal? Because of how we evolved to privilege speech over breathing. In most mammals, the larynx is high in the throat, keeping the airway and esophagus reasonably separate. In humans, however, the larynx descended to enlarge the vocal tract. This made for a more resonant cavity, enabling singing and complex speech, but it also created a shared pipe via which even small amounts of wrongly routed food could cause us to choke. But the evolutionary advantage of advanced communication outweighed the survival risk of occasional choking.

Humans must be understood through this lens: they are so obsessed with talking that they are willing to die to get a few words out. And, as a result, they judge intelligence based on how human-like things sound.